Why Early Language Access Matters More Than Hearing (Part 1): Understanding Language Deprivation

- Toby Overstreet

- 1 minute ago

- 9 min read

Key Points

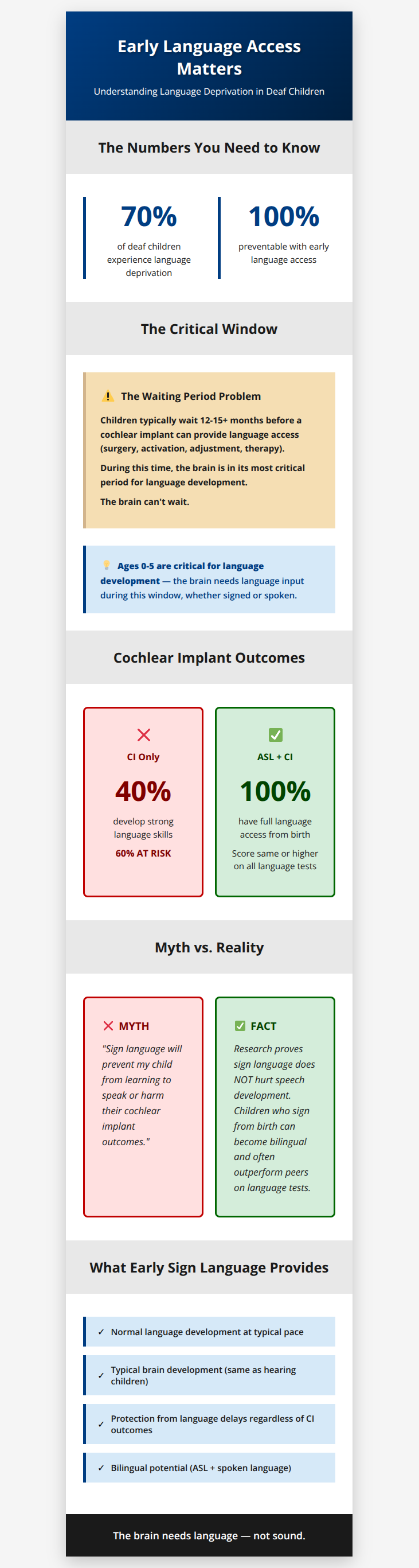

Language deprivation affects up to 70% of deaf children, completely preventable

The brain needs language (signed or spoken) during early childhood

Sign language does NOT prevent speech—research proves this wrong

Cochlear implants work well for only 40% of children when used alone

Early sign language provides full access and protects brain development

Children who sign from birth can become bilingual and develop typically

Table of Contents

When parents find out their child is deaf or hard of hearing, doctors usually talk about one thing: how to help their child hear. They discuss cochlear implants, hearing aids, and speech therapy. Everything focuses on sound.

But here's what many professionals don't stress enough: your child's brain doesn't need sound to learn language. It needs language.

This difference is critical. Watch this in-depth look at language deprivation.

Today, we're talking about something that affects up to 70% of deaf children: language deprivation.[1] This means not getting enough language during childhood. The good news? It's completely preventable.

What Is Language Deprivation?

Language deprivation happens when a child doesn't get enough language—whether spoken or signed—during their first five years of life.

These early years are crucial. A child's brain is building connections at lightning speed, and it needs language to build these connections correctly.

Here's the key point: language deprivation isn't about how a child learns language. It's about whether they have full access to any language at all.

A deaf child surrounded by spoken language they can't fully hear—even with hearing aids or cochlear implants—may be missing out on language.

But a deaf child who learns American Sign Language (ASL) from birth has complete access to language and develops at the same pace as hearing children.

What Happens When Language Is Delayed

The research is clear: children who don't get enough language early in life have different brain structures than those who do—and it doesn't matter if that language is signed or spoken.[2]

Scientists studied brain pathways that handle language. They found that these pathways need early language input to develop correctly. It doesn't matter whether that language comes through hearing or through seeing signs.[3]

Here's what happens when a child doesn't get enough language early on:

The Brain Doesn't Develop Normally: Parts of the brain get smaller and connections change. These changes can't be fixed later.

Grammar Becomes Difficult: People who learn language late struggle with complex sentences and grammar.

Thinking Skills Suffer: Language isn't just for communication—it's how we think and learn. Without early language, children fall behind in school.

Reading Is Harder: Children need a strong first language to learn to read well.

Language Deprivation Syndrome: Long-Term Impact

Professionals working with deaf adults see a pattern called Language Deprivation Syndrome describing challenges in people who didn't get enough language as children:[4][5]

Difficulty becoming fluent in any language

Gaps in world knowledge

Cognitive challenges

Difficulty with emotional regulation

Academic and reading struggles

Higher rates of mental health issues

Dr. Sanjay Gulati's research found that adults who missed out on early language faced serious difficulties, with some showing dangerous behaviors.[4]

The Myth That Sign Language Prevents Speech

Many people believe that teaching a deaf child sign language will stop them from learning to speak or make their cochlear implant work less well.

This is not true. Research proves it's wrong.

There is no evidence that sign language hurts a child's ability to learn spoken language. Research shows that learning sign language early helps children do better overall.

What the Research Shows

Children who sign do just as well—or better—at speaking: Deaf children with implants who learn sign language from birth score the same or higher on language tests compared to hearing children.[6]

Sign language helps the brain: Even brief sign language exposure before and after getting a cochlear implant improves spoken language outcomes.

Bilingualism provides cognitive benefits: Children who use both ASL and English have stronger thinking skills from practicing language switching.

Early sign language builds a foundation: ASL gives children a solid base for learning spoken language later.

This false belief comes from bias—specifically, audism. Tom Humphries, a Deaf scholar, coined the term "audism" in 1975, defining it as "the notion that one is superior based on one's ability to hear or behave in the manner of one who hears."[7] This includes the misconception that ASL interferes with English development. Dr. Mallorie Evans found this bias especially common among professionals working with children ages 0-3.[8]

The Reality of "Waiting" for a Cochlear Implant

Many parents are told to focus only on spoken language and avoid sign language while waiting for their child's cochlear implant.

The Timeline Gap

The FDA recently approved cochlear implants for children as young as 7 months old (December 2025), though many centers still use the previous standard of 9-12 months.[9] After surgery, the device requires a healing period of 3-4 weeks before activation.[10]

By the time language becomes accessible through the implant, children have typically missed 10-11+ months of critical development.

The brain desperately needs language during this time, building pathways for all future learning.

Without accessible language, children experience deprivation.

Cochlear Implants Are Not a Guarantee

Cochlear implants work differently for different children, and there's no way to predict outcomes.

Research on people who can hear normally in one ear and have an implant in the other shows that implant sound can be unclear, especially for speech.[11]

Most children with implants still score lower on language tests than hearing children.[12]

The National Association of the Deaf reports that only about 40% of deaf children with cochlear implants develop strong language skills when using the implant alone without sign language.[13]

This means 60%—more than half—are at serious risk if they rely only on the implant.

The "Wait and See" Trap

Some doctors advise: "Try the implant first. If it doesn't work well, teach sign language later."

This ignores brain development. By the time you realize the implant isn't providing adequate access, the critical period may have passed.

Your child's brain can't wait.

Dr. Wyatte Hall emphasizes: "Parents and professionals should be aware that the cochlear implant is currently unreliable as a standalone first-language intervention for the deaf child."[14]

What Early Sign Language Provides

So what happens when deaf children learn sign language from birth?

Normal language development: Deaf children with signing parents develop just like hearing children, reaching milestones on the same timeline.[15]

Typical brain development: Brain scans show deaf children who learn sign language from birth have the same brain development as hearing children learning spoken language.

Protection from language delays: Even if a cochlear implant doesn't work well later, these children already have complete language access.

Bilingual potential: Research shows children who sign from birth can "learn to speak at a normal level for their age... sign language doesn't hurt a deaf child's ability to learn spoken language after they get an implant."[6]

In Part 2, we'll discuss which children are most at risk, what parents need to know, and what you can do right now to protect your child.

Footnotes

National Association of the Deaf. (2023). "Implications of Language Deprivation for Young Deaf, DeafBlind, DeafDisabled, and Hard of Hearing Children." Based on existing research literature, "many deaf children – perhaps as many as 70% – are deprived of language." https://www.nad.org/implications-of-language-deprivation-for-young-deaf-deafblind-deafdisabled-and-hard-of-hearing-children/ ↩

Penicaud, S., et al. (2013). "Structural brain changes linked to delayed first language acquisition in congenitally deaf individuals." NeuroImage, 66, 42-49. Brain imaging showed that delayed language acquisition significantly affects brain structure in language regions. ↩

Cheng, Q., et al. (2019). "Effects of Early Language Deprivation on Brain Connectivity." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 320. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00320/full — Early language deprivation affects brain language pathways, regardless of whether the language is signed or spoken. ↩

Gulati, S. (2014). Language deprivation syndrome. ASL Lecture Series. Dr. Gulati shared research about 98 people with language deprivation who came to his clinic. He found that people who didn't learn sign language until later in life and had weaker sign language skills were much more likely to exhibit dangerous behavior toward others. More information at Center for Atypical Language Interpreting, Northeastern University: https://cssh.northeastern.edu/cali/language-deprivation-syndrome/ ↩ ↩

Hall, W. C., Levin, L. L., & Anderson, M. L. (2017). "Language Deprivation Syndrome: A Possible Neurodevelopmental Disorder with Sociocultural Origins." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 761-776. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5469702/ — Comprehensive review proposing Language Deprivation Syndrome as a distinct condition with symptoms including language dysfluency, knowledge gaps, and cognitive/behavioral difficulties. ↩

Hall, W. C. (2017). "What You Don't Know Can Hurt You: The Risk of Language Deprivation by Impairing Sign Language Development in Deaf Children." Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 961-965. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5392137/ — This commentary synthesizes research on signing and non-signing children with cochlear implants. Hall references Davidson, K., Lillo-Martin, D., & Chen Pichler, D. (2014). "Spoken English language development among native signing children with cochlear implants." Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19(2), 238-250. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3952677/ — The Davidson study found that "children with CIs who also have deaf signing parents" who "receive exposure to a full natural sign language (American Sign Language, ASL) from birth" showed "comparable English scores for the CI and hearing groups on a variety of standardized language measures, exceeding previously reported scores for children with CIs." The conclusion: "natural sign language input does no harm and may mitigate negative effects of early auditory deprivation for spoken language development." ↩ ↩

Humphries, T. (1977). Communicating Across Cultures (Deaf/Hearing) and Language Learning [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Union Graduate School. Humphries originally defined audism as "the notion that one is superior based on one's ability to hear or behave in the manner of one who hears." More information: Gallaudet University Deaf Studies Digital Journal, Audism Resources. https://gallaudet.edu/deaf-studies/deaf-studies-digital-journal/audism-resources/ ↩

Evans, M. (2021). "Implicit Bias in Audiology: How Does It Affect Families of Deaf or Hard of Hearing Children?" The Hearing Journal, 74(10), 16-17. "Linguistic bias is particularly entrenched in pediatric audiology, especially in those who work with children ages 0-3 years." https://journals.lww.com/thehearingjournal/fulltext/2021/10000/implicit_bias_in_audiology__how_does_it_affect.9.aspx ↩

CNN. (2025). "Babies as young as 7 months now have access to 'transformative' cochlear implants." Medical technology company MED-EL announced that the US Food and Drug Administration has approved expanding the use of its Synchrony cochlear implants to children as young as 7 months who have bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss. https://www.cnn.com/2025/12/05/health/cochlear-implants-infants-fda-approval-wellness — Prior FDA approvals: age 2+ (1990), age 12+ months (2000), age 9+ months (2020). ↩

Bishop, G., & Kelsall, D. C. (2024). "Early Cochlear Implant Activation: Clinical and Surgical Implementation Considerations." The Hearing Review. "Traditionally, patients wait 3-4 weeks after surgery before having their cochlear implant sound processor activated." https://hearingreview.com/hearing-products/implants-bone-conduction/cochlear-implants/early-cochlear-implant-activation-clinical-and-surgical-implementation-considerations ↩

Dorman, M. F., Natale, S. C., Butts, A. M., Zeitler, D. M., & Carlson, M. L. (2017). "The sound quality of cochlear implants: Studies with single-sided deaf patients." Otology & Neurotology, 38(8), e268-e273. Researchers tested people who can hear normally in one ear and have a cochlear implant in the other ear. They played different sounds and asked these people to pick which ones sounded most like what they hear through their implant. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5606248/ ↩

Multiple studies document high variability in cochlear implant outcomes. Niparko, J. K., et al. (2010). "Spoken language development in children following cochlear implantation." JAMA, 303(15), 1498-1506. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3073449/ — Blamey, P., et al. (2013). "Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients." Audiology and Neurotology, 18(1), 36-47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23095305/ — Studies show that results vary widely from person to person after getting a cochlear implant. How well it works depends on the individual child, even when we know things like how old they were when they got it. ↩

National Association of the Deaf. (2021). "Position Statement On Early Cognitive and Language Development and Education of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children." https://www.nad.org/about-us/position-statements/position-statement-on-early-cognitive-and-language-development-and-education-of-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing-children/ — Quote: "Such informed estimates indicate that no more then 40 percent of deaf and hard of hearing children who have cochlear implants but do not use sign language get a linguistic benefit from the device. Unfortunately, the remaining 60%, an unacceptably high number (even 5% is too much), are at risk of linguistic deprivation when they are given cochlear implants and speech only exposure to language." ↩

Hall, W. C. (2017). "What You Don't Know Can Hurt You: The Risk of Language Deprivation by Impairing Sign Language Development in Deaf Children." Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 961-965. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5392137/ — Hall states: "Parents and professionals should be aware that the cochlear implant is currently unreliable as a standalone first-language intervention for the deaf child," citing Humphries, T., et al. (2012). "Language acquisition for deaf children: Reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches." Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 16. https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-9-16 — The Humphries team includes researchers affiliated with the NAD and their work has been cited extensively by the NAD in position statements on early language access for deaf children. ↩

Meier, R. P., & Newport, E. L. (1990). "Out of the hands of babes: On a possible sign advantage in language acquisition." Language, 66(1), 1-23. Deaf children with signing parents reach language milestones on the same timeline as hearing children. ↩

Comments